Genre...

Horror, some science, and the uncanny. And Stories.

Welcome back to the halfway stage in this little experiment. This is the sixth of twelve newsletters previewing, and peering behind the curtain that shrouds From Bitter Ground, an immersive hybrid book/digital experience that’s going to be released in April.

Where were we?

Ah, yes, the uncanny, and science.

Let’s start with a question - Is it better that a piece of genre fiction stays in its lane? In that, does horror need an explanation, or is it better left in an unknowable state? Are things somehow made less powerful when there’s a scientific (or pseudo scientific) justification applied to their structure, or meaning, or purpose. Do we need to know what the Star Child means at the end of 2001, or is it enough to be taken on Kubrick’s joyride and come out the other end with our souls renewed? Does having an inkling that Möbius strips are a way of reading David Lynch’s Lost Highway deplete the experience of watching the film, or is that a necessary scaffold by which to read the story as it unfolds on the screen?

You have your own answers, I’m sure, but as this is my newsletter, I get to hold court.

No, I don’t think science and the uncanny are wholly compatible. And yet they are, and I frequently find myself looking for those connections, and building that scaffold.

I’m drawn to weird fiction, and this year I’ve also found myself having opinions on the surge of AI art (and AI/Machine Learning in general) that’s peppered across the internet. Mostly negative opinions, but something that does interest me about what happens when a machine tries to conjure something best left to human imagination and craft is the sheer inhumanity of the work generated. We can’t help but see through our own eyes, and to step away from that perspective is very difficult, and for most of us, an impossible ask. Yet it’s the thing that I do like about AI engines and the work they’re prompted to create. The machine might be able to parse a banana in a semi-realistic manner (it can’t, yet, do the same thing for fingers and hands), but if its asked to ‘imagine’ an environment that’s tinged with something out of our own frame of reference, then it does so with properly alien results. I know that a lot of that is down to the prompt, and the source material that the software has been trained on, but it does unsettle, and I wish we’d see more conversation about that affect of these new tools. Mimicking fantasy or SF artists (mimicking is too light a word - this is theft) is, is seems, the lowest hanging fruit in the orchard.

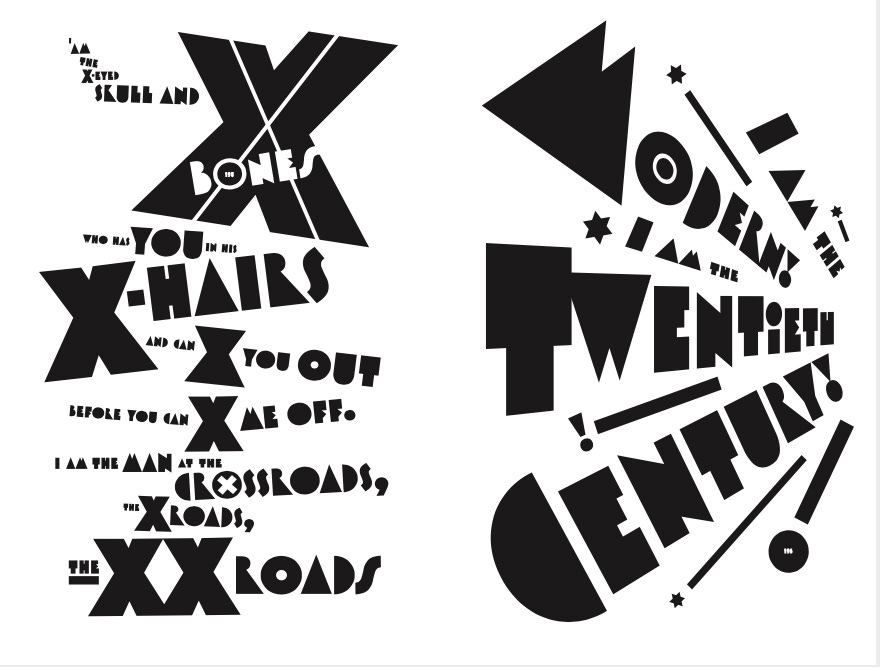

Back to immersion though. Immersive works have proven themselves good at presenting a world that’s just a little to the left of normal. Or put another way, unsettling their audiences. That unease, the moment when something is glimpsed out of the corner of your eye, or heard, or sensed, is the hook to a successful immersive moment. It relies on the familiar becoming, just for an instant, unfamiliar. To achieve that, From Bitter Ground originally had science at its heart, a leap of ‘what if’. I was reading a lot of what might easily be called popular physics while I was writing the first drafts, and I’d just read Rian Hughes’ XX, the heart of which is a really interesting rendition of 20th century art through the medium of typographic experimentation1. I was toying with the form that this work would take, the idea that there would be a pair of books that would challenge the idea of reading them as objects, and instead demand a different approach2, and I had a lot of notes about how our universe is likely to end. My favourite, incidentally, is vacuum decay. I was playing with this being about facing that moment, about the reveal within the work being that the universe had already ended and what you were experiencing was a bubble of reality that was left behind, that hadn’t been destroyed yet, and when it ended then that would really be it. Game over 3.

But it didn’t work with the thing I wanted to write, which was spinning out from having read about the origins of the Big Bang, and asking myself why the man who first theorised it was a thing would have been a Priest, of all people. The first sketches of From Bitter Ground were all about the science, were all about what would happen if the laws of physics started to collapse, or more accurately, misbehave. I’ll talk about the process of killing your favourites when I get to week 10, but the short version is that as the piece began to form, and I asked more questions about what a Catholic Priest from Belgium was doing with Einstein and Hubble, then the whole tenor of the work changed, and that initial reliance on science was replaced and altered somehow by towering horror.

It’s also down to a podcast.

Weird Studies has been running for several years, and I’ve listened for the last two. Phil Ford and J. F. Martel have introduced me to new ways of approaching liminality, and especially the idea of Zones, of what they contain, and what they demarcate. The podcast as a whole is a teeny bit too esoteric for my complete comfort, but there isn’t an episode that doesn’t contain something of interest, something that sparks an idea, or a different take. Listening to it, especially over the last few months, as the piece has neared completion, has been an object lesson in how to consider your audience. Your reader is a person, and if the work you’re making is attendant to that being-ness, then what you’re doing is guiding their perceptions and what they think they see. How they perceive the world you’ve created together. You’re asking them to see through your eyes (all writing does that), and that’s the key, for me at least. What do I see when I’m writing this, and how do I bring you into that space, and see the world we’re making as I do? And accordingly, bring your own eyes to it as well.

I cut my storytelling teeth in RPGs, many many years ago. I was a good player, I think, but a better DM. The degree to which a good, participatory adventure is a collaboration between the person behind the screen and the players who’ve agreed to spend several hours in their company was something I learned on the job, and by trial and error. That role-playing games are, in essence, storytelling experiences is something that wasn’t foregrounded when I started playing them in (ahem), the early 1980s - it emerged as a quality pretty quickly, but it did so alongside my getting comfortable with what I was spending my weekends on, and that learning by doing was a big part of my continued affection for the form. (It’s also, with a note of surprised gratitude, why I’m so glad These Pages found an audience in the gaming community - I didn’t expect that to happen, but I’m delighted that it did, and looking back now, it is an obvious facet of immersive works that we (that’s a personal ‘we’) have not really addressed as wholeheartedly as we might have done.

There’s more connective tissue in From Bitter Ground to RPGs then. It’s not an RPG, but it is a piece of work that acknowledges the debt. It is, I hope, about being somewhere, and is reflective of how your presence in that space actually operates.

That it’s a horror piece though is possibly problematic. I’m probably not going to lead on this when it’s released, and that’s mostly down to how horror is, I think, perceived. I might be wrong, but the tenor of the kind of horror I’m reaching for here isn’t (as I suggested two weeks ago) about body horror, or jump scares. It’s a sublime horror, I hope. It’s what happens when the root of the 20th century comes calling for the 21st. When the story you’re a part of, because it’s happening to you, has something utterly other at the heart of it. Something (thanks Phil and J. F.) Weird.

Next time, book design and (finally!) circular reading.

A final aside, thinking about science and writing and peculiar renditions of physics. When the revival of Dr Who was announced, back in 2004, I wanted someone in the showrunning team to call and ask ‘how do you see the TARDIS working?’. Not that it was ever going to happen, but my headcanon TARDIS doesn’t move, and certainly doesn’t fly (although hats off to Russell T Davies and Steven Moffat for making the physicality of the TARDIS in flight a thing). The word that used to be used for the TARDIS ‘taking off’ was dematerialising, and my TARDIS sits there, in its own pocket dimension whilst the universe moves around it. It materialises (as a Police Box, circa 1963) as that’s the only ‘aspect’ of it that can manifest in our universe, and so the chameleon circuit is really a mask for an extradimensional portal that’s opened up from our reality to another one, that’s within the Time Vortex. The TARDIS is bigger on the inside because it’s not in our universe, and so it never ‘flies’, rather the world of matter is shaped around it each time it appears.

What, did you think you were coming here for comics? I’m all about experimental typography..

More on that next week

I might still use that for a piece, so I’m calling bagsie on it.