Book Design

an essay on form and content

Hi, and welcome to the seventh in a series of twelve short essay newsletters in which I get to ramble about the creative process and explore some ‘why’s of immersive design. These all relate to From Bitter Ground - released in April 2023, and available for pre-order in a week or three. Maybe.

On my desk here is a box that’s made of two books, both of them pretty aged (as opposed to old) - a copy of Darwin’s Descent of Man and Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. It’s been made into a desk-tidy - the Darwin is a drawer, and the Doyle a little box on top. Actually, on closer examination, the hard covers and spine have been glued onto a pair of boxes, which have been sanded into a gentle curve and painted to look like a paper block. It’s probably from Esty.

It was ‘gifted’ to me by Jo Lansdowne, whilst tidying the Pervasive Media Studio. That, or it was going to be ‘recycled’.

The thing I like most about it is that it’s still recognisably bookish. It’s bookishness has been diminished by it’s re-imagination as a desk-tidy, but not completely removed. It looks like a book, and while it’s no longer capable of being read, it does call to that facility somehow.

And that’s where we’ll begin this week. What a book is, and how we relate to it.

Also, we’re over halfway through, so I think we can start talking about the project itself now.

Why a book?

Because it’s a thing. And things are recognisable, and familiar. We know how to read a book, even though we might not know how to read an immersive experience. So a book, however it is used, acts as an anchor for the participant. It’s a form they’re used to, and is (like a cinema or theatre ticket), evidence that you have a stake in this. James Bridle talks about books on shelves being evidence of your personal history - you know who you were when you bought a copy of x, you remember the provenance of that book, of why it stays on your shelf - and that’s a facet of what I’m doing here too.

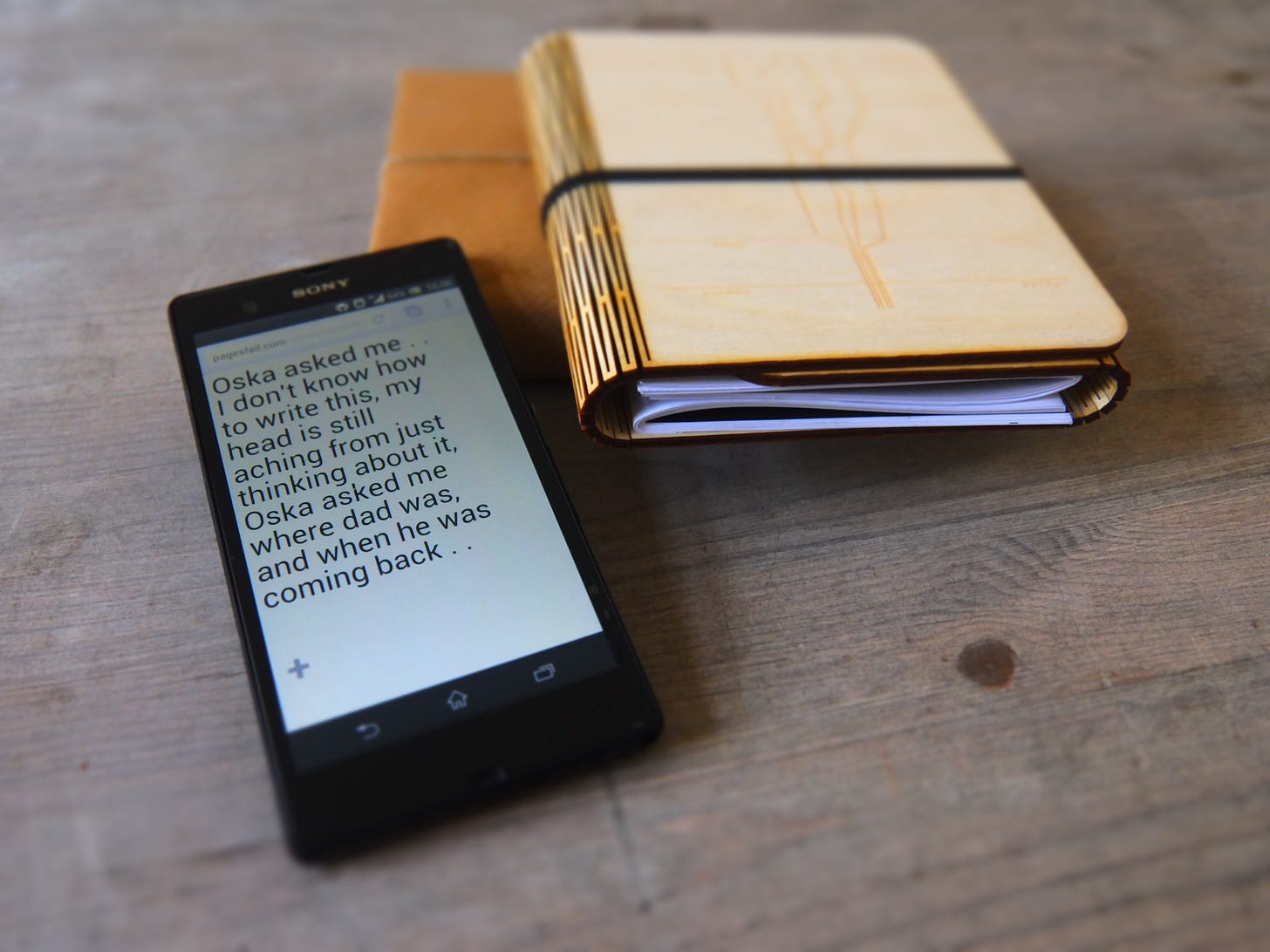

And there’s a thing about what we value too, that feels a bit grubby, but I’ll mention it anyway. We’re very used to digital things being free, or close to free. It was a factor in the way we released the first edition of These Pages Fall Like Ash in 2013 (with due thanks and immense gratitude to Clare Reddington for making us face that). That perception might have changed in the last few years, but I frankly doubt it. The wooden book in 2013 was a ticket, a statement of intent, and a thing that you owned as a result. That you parted with money for.

The second edition of These Pages went on sale for £20. That was based on a book-pricing model, and because it was a round number (we split the revenue between the authoring team, so it made that less of a headache). From Bitter Ground will be £25, and for that you get two copies of the book1. I think the value we attach to physical things over their digital equivalent is a topic that hasn’t gone away in the last 10 years, and I’m really interested in any thoughts you all might have about that. These projects cost money to make, and while I’m not trying to make a living from them (I have the privilege of an academic post), they do need to pay for themselves. For Bitter Ground, I thought combining the price was a good idea - the books are (I hope) beautiful things in their own right, but they’re only part of the whole work. Technically £12.50 for each participant is cheaper than These Pages, but I’m also aware we’re in a global recession / cost of living crisis, so don’t want to overprice things.

Also - nobody knows how to actually cost these things - what is it worth? Is it the price of a theatre ticket? A hardback book? A limited edition book? A Secret Cinema ticket? A Punchdrunk performance? Sarah Crown (the brilliant Literature Director for Arts Council England) challenged us at the end of Ambient Literature, stating plainly that ‘if you don’t figure out how to charge, then it’ll be free forever’. Sarah’s right, and tackling that head-on is really important, especially as this is an emerging form and the decisions we make now have an impact down the line, for us and for other creators. We’re not going to get it right every time, but we aren’t going to duck that conversation either.

But, back to books. I make books, and I work with books. The thingness of a book, the facticity of it, the ontology and history of them, the material presence, and readability, and the universality. I make books that (the easy shorthand) don’t behave like books, that try in their own way to defy expectation. And I’m very very disappointed with over 90% of publishing2.

For this reason:

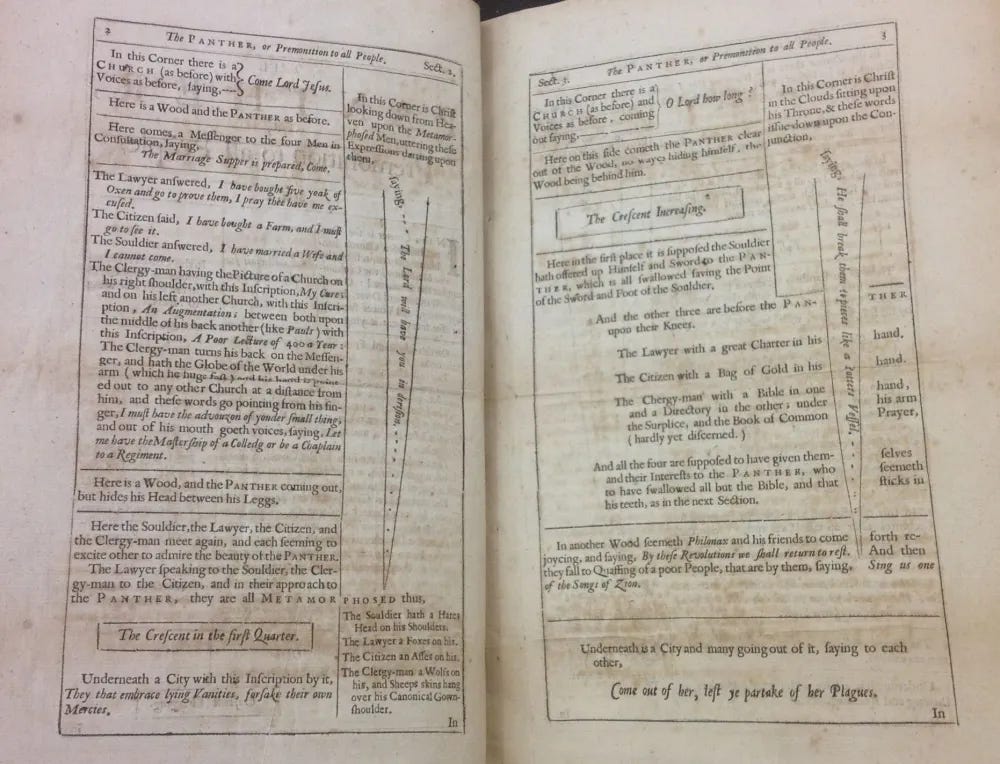

The book, as a form, has been a given thing for nigh on 600 years. Before that too, but we get to call those incunabula - books that are recognisably books, but made before c.1501, in the earliest days of the printing press in Europe. In that time, the form of the thing has settled, through experimentation, and innovation, and Ian Gadd will explain far better than I ever could the varied history of the book as you think you know it. And in the 20th century, the mass-market paperback fixed the form through a combination of at-scale production process, point of sales demand and audience development into what we know it to be now.

And that’s, largely, it. For that 90+% of publishers, it’s a done thing. No experiments, no innovation, no challenge.

FOR FUCK’S SAKE - we know what a book is now - why can’t you at least try to make the thing a little more interesting?

There. Got that out of my system.

What frustrates me, constantly, is the paucity of real, genuine innovation in form. I deliberately mentioned Rian Hughes’ XX last week, and that can join Daniel James’ The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas, Stephen Hall’s The Raw Shark Texts, Mark Z Danielewski’s House of Leaves, BS Johnson’s The Unfortunates, Stephen J Clark’s In Delirium’s Circle, Jonathan Safran Foer’s Tree of Codes, Marc Saporta’s Composition No.1, T. M. Wolf’s Sound, and Doug Dorst and JJ Abrams’ S as the pretty bloody narrow selection of experimental books that have gained any traction in the last twenty years3.

Come. On.

We figured out printing at scale in the 1930s; cheap, stable Desktop Publishing from the mid 1990’s onward; we have decent print-on-demand from (essentially) a pdf file and have done for years. Publishing, what’s your excuse?

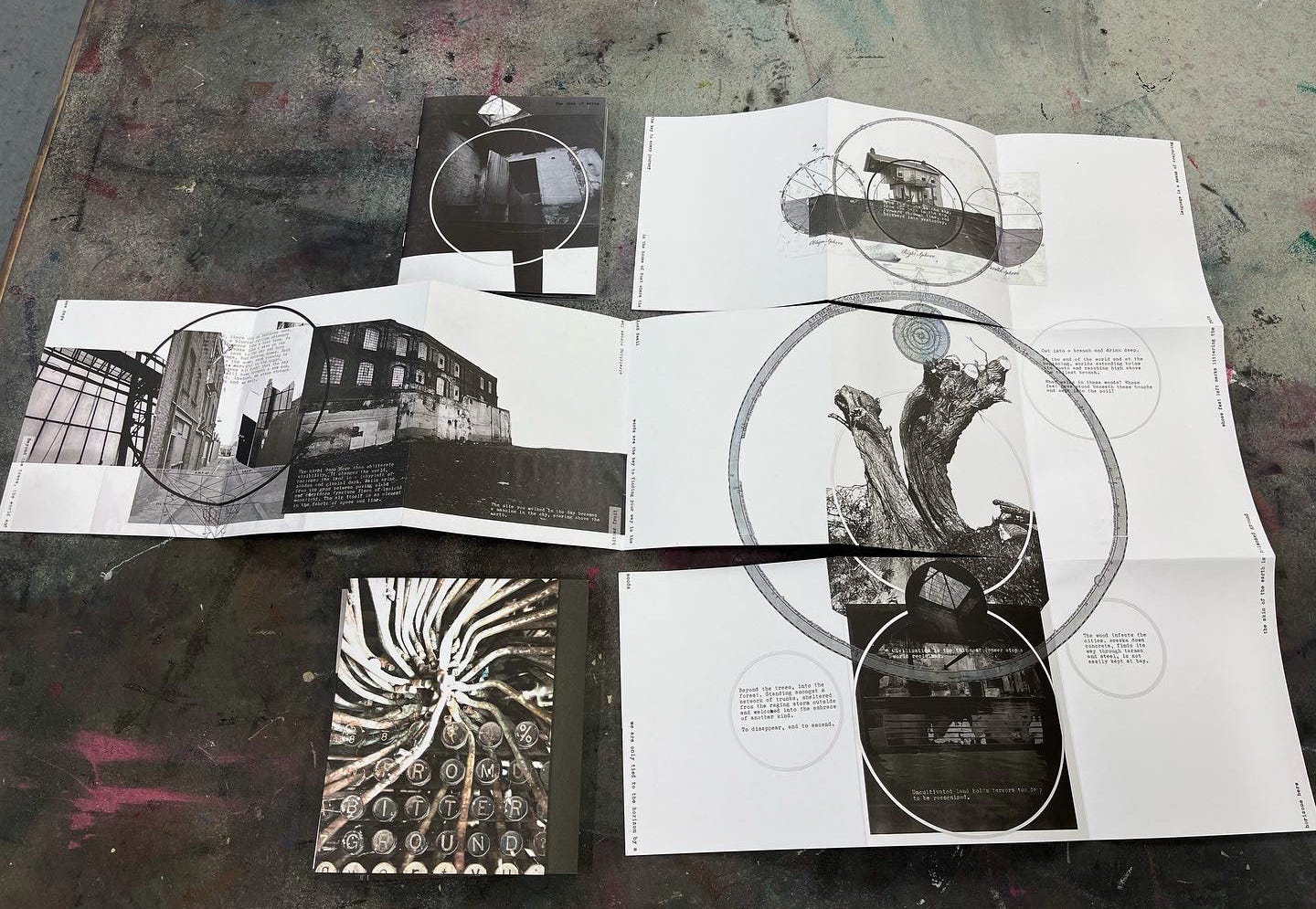

What I wanted for From Bitter Ground was to explore how that experiential space relates to the design and form of the books that form part of it. The book that holds the piece together is a concertina. It is seven panels long, on each side, including a cover. There’s very little text, and instead a series of images are printed onto each successive panel. These have a pattern - one sequence are buildings split or absent, the other are fragments from the trenches of the Great War, but with new material collaged into each photograph. There is text, but it is at best ambiguous, and maybe apparently aleatory. That’s it. That book circles in on itself - depending which cover image you start with, you’ll walk a path through a series of pictures and then begin again with the other cover as you physically turn the book around4. But that’s not all. Nestled inside the last leaf of each sequence is another book. These, at least, have titles. The Book of Entrances and The Book of Exits.And they have text. Sections of prose, that can at least be read against the images on each page. Although one of those pages is nearly A2 in size.

They can be read. I promise you that. But, just as the books that accompanied These Pages Fall Like Ash were a guide, a companion to a story that would emerge from the streets of the space around you, so the books for From Bitter Ground only really come to life during the work itself. There’s a deliberate strategy in how and when you get them too. The prologue for the piece is activated when you place your order, so you’re choosing your site and ‘mapping’ it before you encounter the physical books. That does mean you don’t have a frame of reference beyond the guidance we send you, but it also takes the act of choosing a ‘place’ this will unfold in away from any complication generated by the books. They ‘impose’ on the space after you’ve selected it and experienced the first series of encounters with it. They exist, on their way to you, but anticipated rather than materially present. In that way, I’m hoping that they’re a part of the overall sequence, as much as a layer. They’re going to be difficult to take with you on a walk, so they’re designed to be reflections of the narrative, to open doors and reveal holes afterward and before, rather than during. They will though, sit in your head during the piece too, not a separate thing, but connected through what happens and the links drawn between the experience and the text. The circular reading motif runs within the books, and also across books and immersion, tied together by the reader’s presence within the whole work.

This, then, is the point.

The books are, I hope, thoughtfully designed, and designed to complement and enrich the whole work, so they don’t simply echo content you’ll find across each day of the narrative. Instead, they’ll provide a counterpoint, and a re-reading of the whole piece as you progress through it. That’s what I’ve been trying to do with the synthesis of book design and immersive experience - to reach for a design aesthetic and methodology that does something with the two forms that can’t be done by each on their own.

Book design can be more than we’ve seen. Design (of all kinds) can be sympathetic to the whole, rather just an element in service. This is what good design aspires to in any field - architectural design responds to and informs how people traverse a space, and is informed by them in turn. All I’m asking is that book design (in all its myriad incarnations) aspires to the same thing.

Okay. Next time, technology, platforms for experiencing and some introductions. Thanks for sticking with me. Only five more to go…

I’ll figure out how we do postage for two destinations closer to launch.

Sturgeon’s Law, everyone.

There are undoubtedly more. Those where the set I use to lecture with when I do the long form version of this rant. But even if you add yours to the list (please do in the comments) it’s still a pretty poor showing.

And you thought I dropped Lost Highway in last week for the hell of it…